This week I’ve been thinking about endurance.

I’m nearing the end of a long school year, and there’s a stark difference between the students and teachers who remain motivated and energetic, eager to tackle final projects exploring all they’ve learned this year, and those who are army-crawling their way to the finish line. (I’m both of them, depending on the day.)

It has me thinking about endurance in creative fields, too.

Some of you know my story, but for those of you who are new around here, I wrote and revised six novels over the course of six years before I signed an offer for Heart Check. I learned so much in those years: how to revise a manuscript, how to create satisfying character arcs, how to write pitches and query letters, how to build supportive creative habits and communities, how to persist in the face of challenges. (I am, of course, still and always learning these things.)

One of my most vivid sensory memories from those six years is the feeling of waiting for good news. I could get a response to a query or submission at any time, and any crumb of a win—a reading update, a request, even a kind rejection—would help me endure. I remember wishing for one single email when I woke up in the morning; on the days it arrived, it really did buoy me, reassure me that it was worth continuing down this road in the face of challenges and setbacks, disappointments and self-doubt.

So human, so normal! But the tendency doesn’t go away, does it? As many have discussed, we immediately move our goalposts once we achieve a dream—and then we’re waiting for good news of other kinds, like counting down the days to summer.

I don’t think it’s necessarily bad to have new, more ambitious goals—striving can be healthy. But this month a book, a podcast, and an article collided to make me wonder just what role “wins” play in living a long, thriving, creative life.

A Hidden Brain episode called “Wellness 2.0: Who Do You Want to Be?”, featuring an interview with psychologist Ken Sheldon, reminded me of some things we all know: we’re not great at predicting how achieving our goals will affect us! We think reaching some milestone will make us happy—finally—but when researchers measure its real effect, there’s usually no change. That good old arrival fallacy…

But the episode went further in a way that kind of blew my mind:

“Another thing we found was that it was this paradoxical thing where the students who began with the most idealistic motivation tended to do well. They got good grades in their first year of law school, but that had a corrupting effect where being the highest graders, they became the highest status students and their values shifted in the direction of looking good, having status instead of helping others. And so their idealistic motivation turned into much more self-centered motivation over time…

The irony is the better one does at each stage, the harder it becomes to ask if you are actually doing what it is you want to do. Soon, the systems of carrots and sticks that guides us through adolescence and youth is now driving us through our careers. In one study of 6,000 practicing lawyers, Ken found that many of these professionals prioritize things that the world had decided should make them happy, often at the expense of things that actually made them happy…

Ed Deci found that these two kinds of motivation had different sources of nourishment. Intrinsic motivation springs up from the inside. It's often shaped by interest and curiosity. Extrinsic motivation comes from the outside. Of course, by the time professionals have embarked on a career, they've had 20 or 30 years of carrots and sticks thrown at them by family, by teachers, and by the world. The experiments that Ed Deci ran show that even when people started doing an activity because of interest and curiosity, adding external rewards and punishments had the paradoxical effect of destroying intrinsic motivation.”

Are you hearing that? If we’re not careful, success can ruin the motivation that made something worthwhile in the first place?? It makes sense—if we put too much value on external approval (likes, sales…), we want more, and might be unwilling to risk prioritizing values at odds with those rewards!

Cool. Want to hear something even worse?!

“And so we did these classic experiments showing that when you pay people to do something, it makes them not want to do it anymore. So if you're solving what should be a fun puzzle that almost everybody likes to do, but you're doing it because you get a dollar for each correct solution, and then you're left alone in the room for a five-minute period and you can either do more puzzles or you can pick up a magazine. In that condition, you pick up the magazine or today you bring out your cell phone. On the other hand, the participants in his studies who were just told, "Hey, check out these puzzles, see if you like them." There was no mention of money. When they were left alone in that room, they kept on trying to do new puzzles, they retained their intrinsic motivation.”

Vedantam and Sheldon cite another study, comparing amateur athletes to those who received college scholarships—and found the amateurs enjoyed playing far more.

“You would think that they're so good at the sport, they've spent so much time practicing it, they were able to earn a scholarship, they should be the ones who really continue to like it. The reason that they don't comes down to the fact that they felt very controlled during their college years. They felt like they had to do it, they'd lose their scholarship if they didn't. People were talking about them on the discussion boards, the fans were criticizing them, the coaches were bossing them around. And so when people feel controlled by their environment or their situation, that really tends to undermine their intrinsic motivation. And so as soon as it appears that it's okay to stop doing it, they're prone to go ahead and stop.”

I had to relisten to this part of the podcast, because it created some cognitive dissonance for me. If anything, I’ve gotten hungrier than ever to write in the last year. Maybe because I don’t feel controlled—I feel empowered. By great notes from my editor, encouraging early readers, and the chance to share stories I care about with a wider audience. I don’t want to discount the power of the external, perhaps especially as a story-teller—our words gain meaning when they reach readers, whether it’s a few eager friends or thousands of fans. There’s magic in being seen for your work (not to mention that artists deserve payment, of course).

But the research reminds me that these external cues can shift. I know not everyone will like my work—how do I stay resilient in the face of criticism or disappointment? If you’re starting to feel controlled by extrinsic motivation, how do you keep it from ruining the joy and values that brought you here?

That’s when David Brooks’s piece in The New York Times called “A Surprising Route to the Best Life Possible” (I’m sold) arrived with some answers.

The whole thing is really worth the read, but it begins with a discussion of Haruki Murakami’s approach to writing and running. Murakami complains extensively about how painful running is, how miserable it makes him. Brooks asks:

“Why would he do something that regularly makes him miserable? But when you look around, you see a lot of people out there choosing to do unpleasant things… All around us there are people who endure tedium to learn the violin, who repeatedly fall off stair railings learning to skateboard, who go through the arduous mental labor required to solve a scientific problem… My own chosen form of misery is writing. Of course, this is now how I make a living, so I’m earning extrinsic rewards by writing. But I wrote before money was involved, and I’m sure I’ll write after, and the money itself isn’t sufficient motivation.”

He goes on: “I don’t like to write but I want to write. Getting up and trudging into that office is just what I do. It’s the daily activity that gives structure and meaning to life. I don’t enjoy it, but I care about it.”

Brooks argues we often think humans “operate by a hedonic or utilitarian logic,” avoiding pain and seeking pleasure, reducing effort wherever possible. But:

“When it comes to the things we really care about — vocation, family, identity, whatever gives our lives purpose — we are operating by a different logic, which is the logic of passionate desire and often painful effort.”

Brooks traces the ways we find this thing we care about—perhaps a group of people who seem inspiring, who we wish to be like; perhaps a moment of “contact with beauty,” the first time we encounter an awe-inspiring piece of art that gives us that this is what it’s all about zing.

Then we enter a stage of curiosity where we’re desperate to learn as much as we can. Interestingly to me as both a writer and educator, he argues that curiosity needs to be transformed into a skill. Effectively curious people have three things:

cognitive enthusiasm (they like to explore mysteries and think about new things)

cognitive confidence (they are brave enough to tackle hard problems)

cognitive complexity (they don’t settle for simple stereotypes)

All of this reinforces lots of what I’ve been thinking about: the importance of ongoing learning, new challenges, experimentation and exploration. But I’m still unsure it settles the question raised by the Hidden Brain podcast—until Brooks begins talking about the next stage, the discrepancy. In other words, the moment we notice the gap between what we know or can do and what we want to know or be able to do.

“Whether it is ballet, engineering or parenting, the seeker is humble enough to see where she falls short, inspired enough to set a high ideal and confident in her ability to close the gap…

Wanting flows from a sense of discrepancy. Based on the work of various psychologists, we could say that there are at least four basic psychological needs: for autonomy, belonging, competence and meaning. Of those, the drive for competence doesn’t get enough press. No matter how trivial an activity might be, most people seem to feel an innate need to get better at it — whether it’s kids learning double Dutch, me just shooting baskets in the driveway or somebody else proud at how much better he’s getting at flipping pancakes. Whenever you’re seeking improvement, you’re putting yourself on the edge of your abilities, on the hazardous cliff edge of life, and a little built-in thrill accompanies each accomplishment.”

He compares those ensconced in their craft to those living a “Zone 2” life, a term exercise buffs might recognize—you’re not burning out, but are making steady, persistent progress.

“They live with an offensive spirit. They are drawn by some positive attraction, not driven by a fear of failure. They perceive obstacles as challenges, not threats. On their good days, they’ve assigned themselves the right level of difficulty. Happiness is usually not getting what you want or living with ease; it is living, from one hour to the next, at a level of just manageable difficulty.

By the time you’ve reached craftsman status, you don’t just love the product, you love the process, the tiny disciplines, the long hours, the remorseless work. You may want to be a rock star, but if you don’t love the arduous process of making music and touring, you won’t succeed. The craftsman has internalized knowledge of the field so she can work by intuition, using her repertoire of moves, relying on hunches, not rules.”

He then blows my mind by revealing the original definition of leisure: not relaxing, as we think today. But “the state of mind we are in when we are doing what we intrinsically want to do.”

“A person at leisure is the opposite of a person who wants to be an influencer. She is driven by internal propulsion, not for outward display. When that is your mentality, it alters your attitude toward the suffering involved in the process of growth. The drudgery of the work feels like the unfurling of your very nature — a chef endlessly cutting vegetables, a bricklayer endlessly laying brick. One falls into a rhythm that is characteristically one’s own.”

Brooks writes, “that kind of stamina flows only from a desire so steady it almost doesn’t make sense… life is at its highest when passion takes us far beyond what evolution requires, when we’re committed to something beyond any utilitarian logic.”

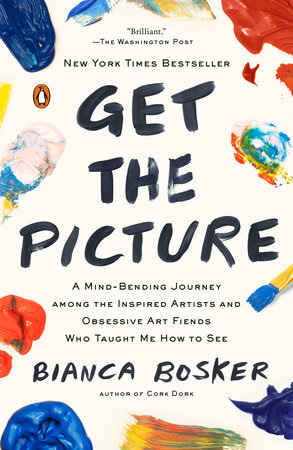

Let me add one final matryoshka doll to this essay: a piece on Bianca Bosker’s book Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See, “Appreciating Life and Creating a Life Worth Appreciating.” The whole book is great, but the article gives a good taste of what’s inside.

Bosker’s ideas about being present with art reminded me of some points Vedantam makes about mindfulness as an antidote to societal conditioning—pausing to be present and curious about our desires to ensure we don’t succumb to extrinsic rewards that are actually distancing us from ourselves.

“Paying attention to art helps us fight the reducing tendencies of our minds. We think we see like video cameras, objectively recording everything around us, but what’s actually happening is we have filters of expectation that dismiss, prioritize, and categorize all the raw data coming in, compressing our reality. Art helps us yank off the filters by introducing novel experiences and images that knock our brains off their axes and make our minds jump the curb… I suggest that when you’re looking at art, you stay in the work itself, slowing down and noticing things about it… If you’re willing to spend time with art, it will work its magic on you.”

So. Creating art, experiencing art, pursuing an artistic life—maybe it’s worth it not for intrinsic or extrinsic motivation, but something else entirely?

That’s where Vedantam and Sheldon’s answer comes in. They conclude by offering us a third type of motivation: not intrinsic or extrinsic, but identified.

“Identified motivation is the kind where it's not that you're doing it because it's fun and interesting. Instead, it's you're doing it because it's meaningful. It expresses your values and it's important to you. And so even when intrinsic motivation fails, identified motivation can still keep going because it believes in the journey, even if the journey is now becoming more and more painful.”

Sounds like a rhythm that’s characteristically one’s own.

Even if clinging to our original pure intrinsic motivation is challenging—because how could that not change, once you exit the beautiful, wonderful amateur phase and strive for a more professional one?—we don’t have to over-identify with the extrinsic, either. We all know that can change, too.

But identified motivation has an endurance I can believe in. I write because it’s the best way I know to understand and express myself, the most magical way to connect with others, the most surefire way to tap into a flow state where nothing else matters. Perhaps discovering that motivation was a far more crucial takeaway than any revision tool from those first six years of striving—and perhaps feeling the “unfurling of my very nature” is what makes that striving feel healthy, not controlled.

I bet you’re here because you think something similar. Every time I’ve had a conversation with a discouraged friend, we’ve eventually circled around to something like: but could you really stop? Can you imagine your life without writing?

The only answer is laughter.

If I keep that in mind, days of writing become their own reward—whether an email arrives or not.

Bosker and Brooks both end with far more profound words than I could ever offer, so let me a) encourage you again to read all of these pieces in full, and b) send you off with their conclusions.

First, from Slater’s interview with Bosker:

“Kagoshima’s painting reminds me that art is a choice. It’s a decision to live a life that’s more beautiful, more complex, and more nuanced. Ultimately, art is about appreciating life, but it’s also about creating a life worth appreciating.”

And from Brooks:

“People tend to get melodramatic when they talk about the kind of enchantment I’m describing here, but they are not altogether wrong. The sculptor Henry Moore exaggerated but still captured the essential point: ‘The secret of life is to have a task, something you devote your entire life to, something you bring everything to, every minute of the day for your whole life. And the most important thing is — it must be something you cannot possibly do!’”

What better reminders to start something, to make something, and to never stop?

I hope we all keep creating lives worth appreciating and doing increasingly challenging puzzles every day.

Much love always,

🤍 Emily

Awesome article. This hit for me at a really good time. Thanks for taking the time to share with us all.

This article may be one of my favourite articles that I have read on substack. It’s a powerful reminder that the hardest work (whether it’s writing, building a business or just showing up in the corporate world) isn’t always about motivation. It’s about meaning. I write a lot about the traps of chasing status and success and this essay nails the cost of losing touch with why we started in the first place.